The body is a tool, made to give us the possibility to take action. Without it we would not be able to carry out any idea conceived in our minds, whether it is taking the trash out, winning the olympics or practising yoga asana. As the body is constructed of physical matter, the key to working with the body successfully is to acknowledge this basic law of matter: Form Follows Function. We need to understand our body’s basic architectural structure; its anatomy. We need to know something about how it operates. The pay off is a successful use of your body in all asanas, most likely less injuries and certainly a less strenuous approach. To find them we must start listening. This is the birth of awareness. With the help of our tuning-in, a knowledgeable teacher and perhaps a thorough anatomy book, we can slowly start to understand the architectural structure underneath our skin. Let’s start with a bit of anatomy.

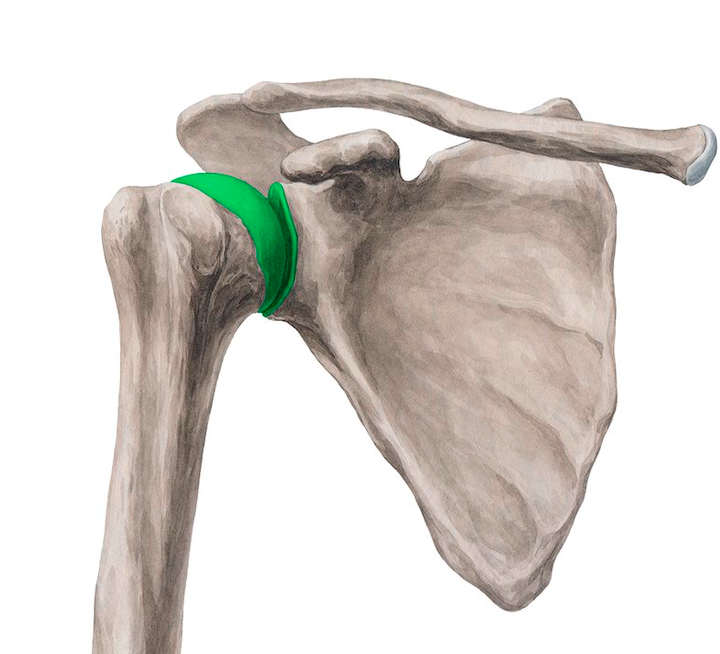

The glenohumeral joint is a ball and socket joint between the scapula - our shoulder blade and the humerus - our upper arm bone. It is one of the most mobile joints in the human body.

Due to its structure it is not as deep and stable as for example a hip joint, which makes it vulnerable especially in weight bearing poses. The head of the humerus, which is relatively large, meets the very shallow surface of the scapula called glenoid fossa. Because of this relationship, the joint is very mobile, with many different arm movements that occur - often compromising the stability.

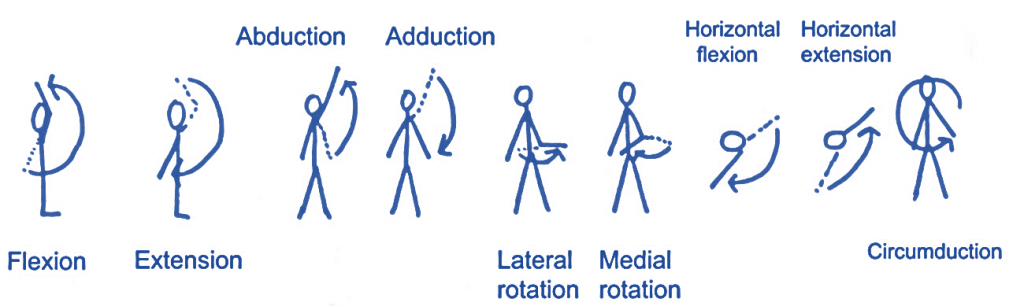

As a ball and socket synovial joint, there is a wide range of movement permitted:

- Extension (upper limb backwards in sagittal plane) – posterior deltoid, latissimus dorsi and teres major.

- Flexion (upper limb forwards in sagittal plane) – pectoralis major, anterior deltoid and coracobrachialis. Biceps brachii weakly assists in forward flexion.

- Abduction (upper limb away from midline in coronal plane):

- The first 0-15 degrees of abduction is produced by the supraspinatus.

- The middle fibres of the deltoid are responsible for the next 15-90 degrees.

- Past 90 degrees, the scapula needs to be rotated to achieve abduction – that is carried out by the trapezius and serratus anterior.

- Adduction (upper limb towards midline in coronal plane) – pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi and teres major.

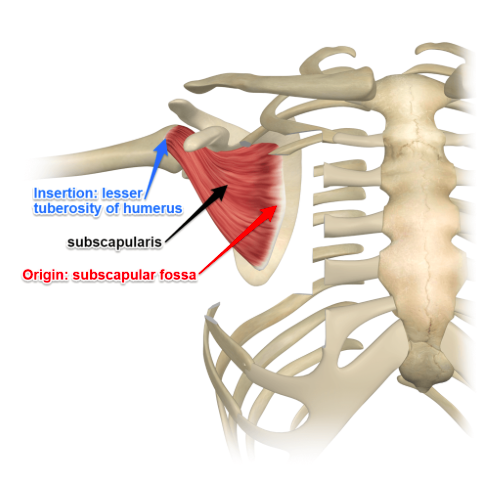

- Internal rotation (rotation towards the midline, so that the thumb is pointing medially) – subscapularis, pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, teres major and anterior deltoid.

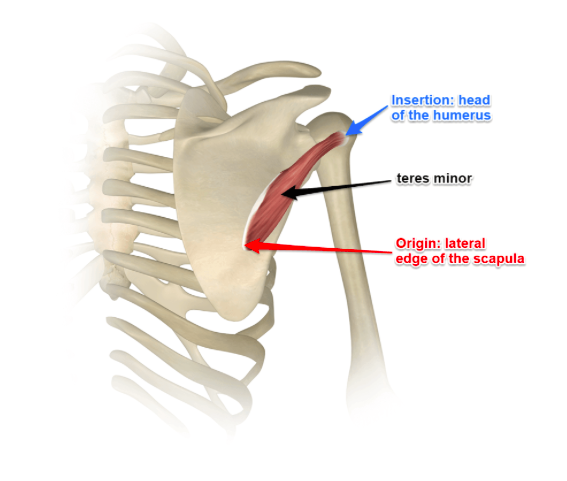

- External rotation (rotation away from the midline, so that the thumb is pointing laterally) – infraspinatus and teres minor.

The Rotator cuffis a group of muscles whose job it is to stabilise GLENO HUMERAL JOINT.

Stabilisation of the shoulder is a complex process shared among the four muscles, whose names can be remembered with the mnemonic SITS: supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis. They all work together providing stability at the joint.

SITS

Ssupraspinatus

Iinfraspinatus

Tteres minor

Ssubscapularis

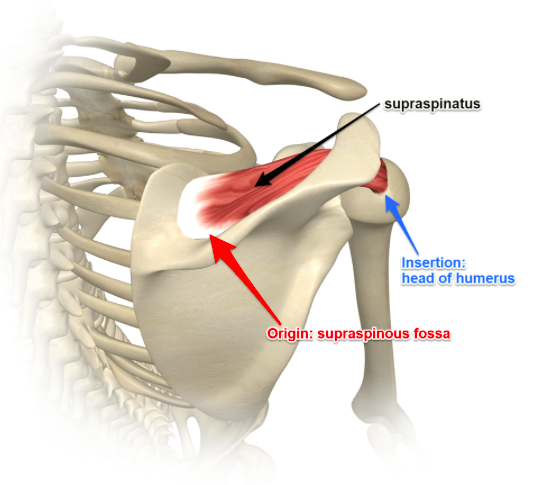

Supra spinatus is the muscle that sits at the top of the scapula and attaches at the head of the humorous. It is responsible for the abduction of the arm.

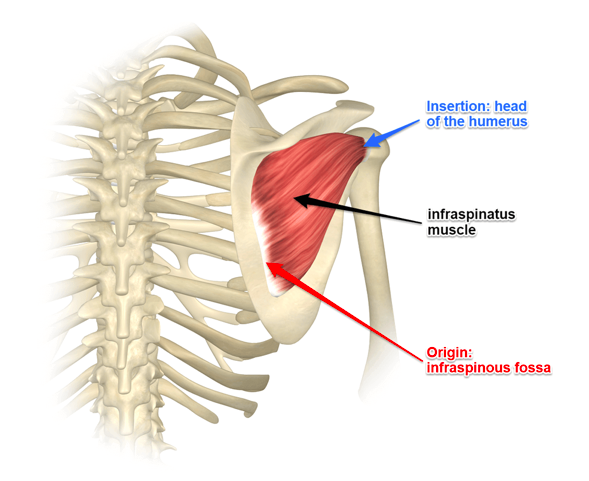

Infraspinatusattaches at the back of the humerus bone below the spine of the scapula and, when the muscle contracts, it externally rotates the upper arm bone

TERES MINORhas the same action - it also externally rotates the upper arm bone

We have one internal ROTATOR - subscapularis This muscle lies underneath the surface of the scapula attaching to the front of the humerus head

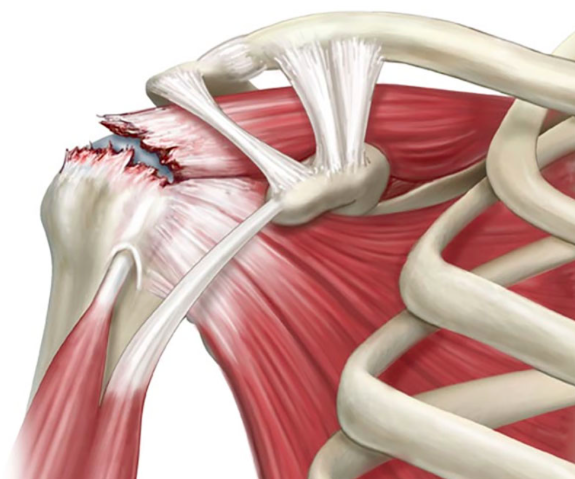

These four muscles — the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis— control the ability to rotate your arms and lift them overhead. Unfortunately, it's not uncommon for the muscles of the rotator cuff to be underworked and therefore weak. This weakness can lead not only to impingement syndrome but also to tears in the rotator cuff muscles themselves, usually near where three of them insert on the greater tuberosity of the humerus. Shoulder impingement is generally caused by repetitive use of your arms overhead in activities such as swimming, tennis, painting, carpentry and even yoga.

Strengthen what is weak - stretch what is tight !

When we compare the internal rotators to the external rotators, it appears that the external rotators are at a disadvantage in creating a balanced muscle tension relationship against the internal rotators. Compound this structural disadvantage with postural imbalances from work, home, physical activity, health, and injuries, and we clearly see how the internal rotators can overwhelm the external rotators. How much of our day is chronically spent with the arms forward (shoulder flexion), arm bones internally rotating, and shoulder blades being drawn forward?

In almost all yogapostures with the arms forward, as in Plank, or overhead, as in Adho Mukha Svanasana, Adho Mukha Vrksasana (Handstand), and Sirsasana, the shoulder is best stabilised with moderate external rotation. This will activate and strengthen the teres minor and infraspinatus.

Perhaps the best yoga prescription for rotator cuff health is to maintain a well-rounded asana practice. Practiced regularly, a variety of standing poses, chest openers, arm balances, and inversions can help you protect this complex and crucial part of your anatomy.